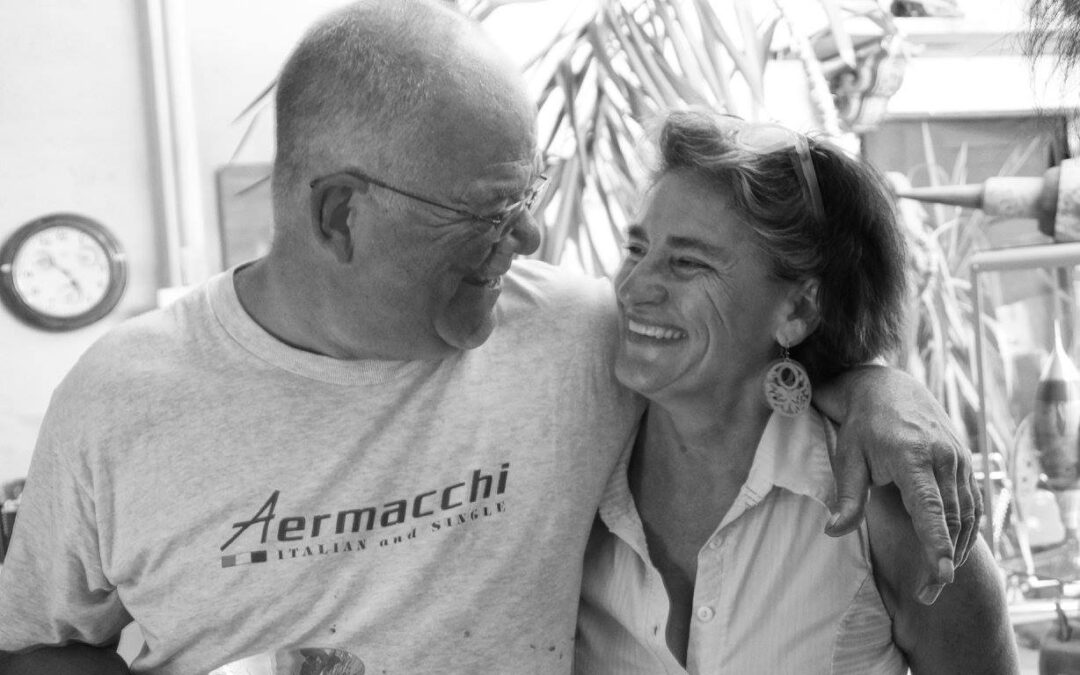

Jocelyn Banyard and Booth Milton are owners of the Vancouver-based prop house White Monkey Design Inc. Jocelyn has had an extensive career in the industry, first setting foot on a film set in 1985. Booth Milton has been working in the film industry for over thirty years making and designing props. Jocelyn Banyard has been working in the film and commercial industry for over thirty years, starting with washing the buckets, and ending in management.

Interview by Madeline Setzer.

1. How did you get started in the industry?

Booth: I was picked up by some production designers while I was graduating from Emily Carr. Then I worked on White Fang 2 while I was working with First Nations artist, Don Yoemans, on totem poles and dugouts for the movie.

2. What drew you to the props world?

Booth: The freedom (sort of), and the endless creativity and challenges of solving impossible demands and timelines. I got to work with the crème of the creative world. It’s like a feeding frenzy of creativity and problem solving. Definitely not money. Imagine a whole life of art making. I was, and still am, lucky… especially being in the Kootenays.

3. What is your involvement in creating the props? What does the process look like?

Booth: Besides terrifying? You have a client who needs the moon – yesterday, for free – because his boss is demanding, because his boss is also demanding, and you are lowest on the totem pole. Film is a ‘can do’ industry. My place is to advise how to get to the finish line financially and creatively. Film says choose two – quality, cost, or timeline. The three don’t go together. Another great thing about film, if you are lucky, is that the funds exist to do what you are asked to do, alongside the cutting edge technology, which sometimes you are actually asked to invent. For instance, I figured out how to goldplate plastic for Disney’s Descendants. As for the process? Make it happen. I got to hire very creative people and the mix of talent in my studio was intense.

4. What is the most challenging prop you’ve been asked to make, and how did you go about accomplishing it?

Booth: Well, too many. I am proud of so many. Even the simple ones were challenging. I enjoyed musicals. I hated horror and violence. But I had to do it all. Teaming up with incredible creatives was always a pleasure, and being part of the colossal projects was a ton of fun. Even the smallest show is incredible; to be part of the team.

5. You’re big on recycling! Do you find the industry wasteful, and if so, how do you go about making it more sustainable?

Booth: There is always an opportunity of being more streamlined and less wasteful. I wish there was a scrapyard here! Recycling is also tied into health and safety. My studio did everything we could to figure out how to keep my crew safe. This includes trying to figure out less toxic ways to build things. Film has a very high early death rate.

6. What are some of the most unique or valuable props in your inventory?

Booth: I have many, and unfortunately I bought a lot of Asian antiques that don’t really fit into a house. I never considered value, so never held onto stuff. Other people were more cognizant and took things. Lots of collectables disappeared. I did not understand the value of this stuff. But I must say, I am very thankful I got to work with and become friends with so many really great First Nations artists.

7. What is the craziest story you have from working on a film set?

Booth: Well, you cannot re-tell. I will in person though – and off the record. Lots of fun and crazy.

8. What’s been your favourite project to work on thus far?

Jocelyn: He has to say me, Jocelyn. But really he loved them all.

Booth: I loved working on The Watchman – the work was hard but I loved the movie; Fantastic Four (I had every shop in Vancouver working with me, and one of them was an Oscar nominee); and X Men and X2: X-Men United – they were all nifty. I also enjoyed going to Zambia and being involved in our NGO projects there.

9. Jocelyn, you started the initiative, ‘Malambo Grassroots’ with your sister to plant trees in Zambia. How did you get involved? What challenges do you face and what’s the most rewarding part of your work?

Jocelyn: I started Malambo after I volunteered with CUSO ‘91-‘94. I’m a grateful immigrant who landed in Nelson in my early teens. This was excessively difficult. I missed everything I understood and entered a culture I had nothing to grasp onto. When I went back with CUSO, there was a huge drought, so I started working with the women I had grown up with (my family has been in the same spot in Zambia for over 100 years – my gran was an early photographer. So many photos. She was interested in the people around her, so Antonia and I are swamped with documentation of the country).

I started with my mom – a women’s income generation project with 33 women. We did a massive exhibit aimed at the international crowd (all working in drought relief – many not even interacting with the population unless they were servants). My mom and I talked to the women. We are both avid photographers, so wove words, history, traditional culture and textile art together. The show was hosted in the capital, and we took a group of the village women to the opening. It was huge and everything sold. When the women came back, they did not even mention the money they had raised when they presented to the full group. They were amazed that white people wanted to hear what they said and listen to their stories.

Since then, I organized the first series of workshops in the country for contemp[orary] Zambian women artists – the first women’s nation art exhibition. Then 25 years later, the second national women’s exhibition.

I am truly thankful to have been able to do this. Malambo Grassroots runs on very little. The Kootenays have really been our backbone, and the input has maximized. Many of our projects don’t need us any more – Zambianized – which I am thankful for, and this was the goal. Since COVID we have done a lot of tree planting. Malambo keeps evolving… so we have done many things. Because the larger Zambian community knows of us, and what we have done in the past (back to my grandparents), we are trusted – and honestly cannot keep up with the requests now – for trees.

We have just started three pilot orchards with schools – food and income – and will try to find funds to grow these and start more. I love Malambo (named after a local chief) and through all these hard days, it keeps me grounded. I love the people I work with in Zambia and the non-city life. When I have hosted people there, all they want is a safari. I tell them, “no, I can get you off the beaten track.” They always tell me they are blown away by making genuine contact with the country and people.

10. What brought you to the Kootenays, and how was it to continue managing a props house located in Vancouver?

Jocelyn: My parents came to Nelson when we immigrated because of the culture, education and art. My family immigrated from Zambia. My father came two weeks early, picked us up from the Vancouver airport in a ‘big American’ car, and took us directly to a supermarket in Richmond. It blew our minds. We had never seen anything like that before – the lights, the variety, the quantity, the freezers. Some of the products on the shelves we had no idea what they were. [My parents] came with $10,000 and four girls. I left when I could not get a job as a young person.

After LVR [Highschool,] I did a year at the college here in Nelson, a year in Selkirk in Castlegar, and then got accepted to UBC, UVic and Emily Carr. I was surprised to be accepted to ECCAD, so I went there thinking I could always do UBC/UVic after. However, once [I] finished ECCAD, I immediately got a job painting and building for commercials for a company in Vancouver. I walked into the company asking for work and the next day I was sign painting enormous pieces. There really was not a job available in Nelson at that time that used my education, so Vancouver was it. I eventually was in management and ran the paint, prop and sculpture department, as well as bidding on jobs, and a few years of doing the bookkeeping as well which was very helpful towards my understanding of small business. After that I had a time in the film union and then walked into White Monkey which was an easy management fit for me. And aside from that, Booth and I were old friends from meeting on our first day at ECCAD. Lots of funny stories.

Two days before the first COVID christmas, Booth and I got our eviction from the City of Vancouver. We did not have a home. We squatted in the studio for security of the building – no water or power in the [aluminum] airstream [trailer] downtown Vancouver. It was our bedroom. Booth eventually ran an extension cord, but it was cold, leaky until we draped an ugly tarp over it, and the toilet and shower were in the studio itself – so across the yard. Cold and wet in the winter time. Booth had been [in the studio building] for 35 years. The building is still not torn down. You could not hire people at that point, so it was extremely difficult.

We closed down during COVID to follow the guidelines of the union, even though we were non-union. The vast majority of our work was through the union and we complied with union guidelines. However, to keep a crew/talent on the team for when COVID was over, we hired two crew and instead of paying ourselves, we paid them. The building was big enough to provide a lot of space to keep social distancing as it was then advised. Having no income with the loss of work, the company survived on savings. We were then given notice to move which was an enormous financial blow, and finding movers was extremely difficult. The financial impact of COVID, the move, plus the mental stress on everyone, was terrible. What was a very healthy, creative stew pot of a business and training/mentoring platform is now gone. White Monkey trained many who ended up in the union or went on to start their own successful businesses.

Thanks to my mum, I was able to come [back] home [to Nelson] and take refuge. I’m now in her old home, which I believe has always been in a woman’s name. It’s one of the early houses in Nelson, built for a worker. We found their signatures when we were renovating – I was 14 [years old] then. We are adapting and thankful. Managing a small business long distance is impossible. A small business needs the owners, hands on. White Monkey (…) survived when all others did not – because of Booth’s excessive output. When we were unable to actually be there, it did not work. It was a great heart break for both of us.

I used to be Booth’s competitor. We actually went to [Emily Carr] together, and remained friends. Over the years I’d call him and say – I’m bidding on such and such. Often he was as well. We’d discuss the approach to how to accomplish the build, choice in materials etc. When my life changed, it was an easy fit for me to start managing his business. He never cared about money – my ex was obsessed – so even though I’m more in the mold of Booth, I saw he had an incredible business that everyone, except him, was benefitting from. One of the big changes I made was towards building for production – it did not make as much income as doing rentals. Booth and the team making custom rentals was definitely more stress free and profitable. As COVID started – I had all inventory rented long term. COVID broke us.

11. White Monkey Design (your props house) is closing. What was the reason behind your decision? What are some of your fondest memories regarding your time there?

Jocelyn: I want to be here, in the Kootenays. I gave my life to film and I want to refocus on family, art and the environment. My fondest memories are the people.

12. What are your plans now for getting involved with the local film industry?

Booth: Any support we can give – we will. Anyone wanting to learn the props side of things – we have the equipment and I brought samples. Both of us have also done production design, and Jocelyn is a scenic painter. We both have trained literally hundreds who have since moved into their own careers in film and done well.

We recently auctioned off the physical property of the business, and this week is our last (April 15, 2023) in Burnaby. COVIDand its associated impacts closed us down after 35 years of being one of the only companies, of our type, to continuously survive and pivot to the various changes in a very precarious industry. We are now exploring our options in Nelson. We are both very thankful to be here and looking forward to being able to have our full focus here.